Women and Running in 1980s Britain

Tracey Loughran, Professor of History at the University of Essex, discusses how women's magazines in 1980s Britain helped shape attitudes towards running as a sport for women

Three words: “running,” “1980s,” and “Britain.” What are you thinking now? If you know your sports history, it might be Steve Ovett taking the 800m gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, or Seb Coe heading off Steve Cram in the 1500m four years later at the Los Angeles Games. Perhaps it's the closing scene of Chariots of Fire, soundtracked by Vangelis' synths. These are iconic images… and they're all of men. Think about women and exercise in the 1980s, and different images come to mind—maybe bright Lycra bodysuits, Jane Fonda workouts, and “Mad Lizzie” on TV-am. The major women's fitness craze of the 1980s was aerobics, not running.

Of course, some women did run. The 1980s saw a “jogging craze” in the UK. Inspired by the success of homegrown track runners, Britons started pounding the streets in unprecedented numbers. The foundation of the London Marathon and the Great North Run in 1981 reflected the growing appetite for mass events. But far more men than women opted to put on their running shoes and get out there—women made up only 4.25% of the field in the inaugural London Marathon.

Women who exercised were likely to prefer aerobics to running for reasons that feel familiar today. Indoor activities meant women weren't at risk of street harassment. If they felt ashamed of their bodies, they could take a women-only class or watch a video. For women with families, home workouts could be the only way to fit exercise into a busy life.

But other factors that discouraged women from running seem more suited to the 1880s than the 1980s. Victorian beliefs that women were physically incapable of strenuous exercise died hard. Women were only admitted to most major marathon races from the early 1970s. It was only in 1984 that women's events in the 3000 meters and the marathon were included in the Los Angeles Olympics, and it wasn't until 1996 that a women's 5000 meters event was included (the distance having been included for men since 1912). Before then, all-male International Olympic Committees felt these distances were too physically demanding.

These beliefs seem ridiculous now, especially in the face of growing evidence that women might be more physically suited to endurance running. But in the 1980s, most media outlets were ambivalent about women's running. Before the internet, most women found out about health issues from newspapers, magazines, and television. What these sources said about running mattered—especially in the absence of highly-visible role models.

These outlets were not encouraging. Newspapers warned women of the health risks of running. A 1982 Daily Mail article headed “Joggers' route to an early grave” was typical. It warned that “regular women runners” could “develop menstrual problems” and cited an “eminent cardiologist” who advised those over 40 to take up “lady-like pursuits” such as golf, tennis, and swimming instead.

Maybe it's not surprising that the Daily Mail, home of the sidebar of shame, wasn't always supportive of women. But for much of the decade, magazines by and for women did little to encourage readers to run either. In the late 1980s nearly 24 million British women read weekly magazines. Looking at these magazines helps us to understand women's attitudes to running—and why these started to change towards the end of the decade.

The most popular weekly titles were Woman and Woman's Own. The average reader of these magazines was imagined as a busy wife and mother. The magazines tried to balance information and entertainment. In their pages, advice on relationships, childcare, and running a household sat alongside articles on contemporary social problems (homelessness, drug addiction, AIDS), health and beauty tips, reader makeovers, and celebrity interviews.

The jogging craze did show up in women's magazines—but in ways that highlighted women's appearance, not their fitness or enjoyment. In the short story “In the Running” (1982), Laura takes up running to spite her boyfriend, who says she looks like a “little butterball” in her yellow tracksuit. As she loses her “spare tire,” she attracts the attention of a male runner and they fall in love. Beauty and romance are women's real goals, this story implies.

Magazines objectified women's bodies in other running-related coverage. A 1980 interview with Susan Anton, star of Goldengirl, a now-forgotten film about a runner “fed special growth and strength serums by her scientist father” who goes on to break all the records, was mainly interested in her “long, golden legs than go on forever.”

Like most athletic women, she had small breasts, and the nipples showed sharp and clear beneath her vest

Even worse was Woman's Own's serialization of former Olympic coach Tom McNab's novel Flanagan's Run, set in the 1930s. The novel charts Kate's battles with sexist disbelief at her running capabilities—but it also lingers on her looks, describing her as “fresh as paint and pretty as a picture” and exuding “a vital, glowing sexuality.” and stating that “like most athletic women, she had small breasts, and the nipples showed sharp and clear beneath her vest.”

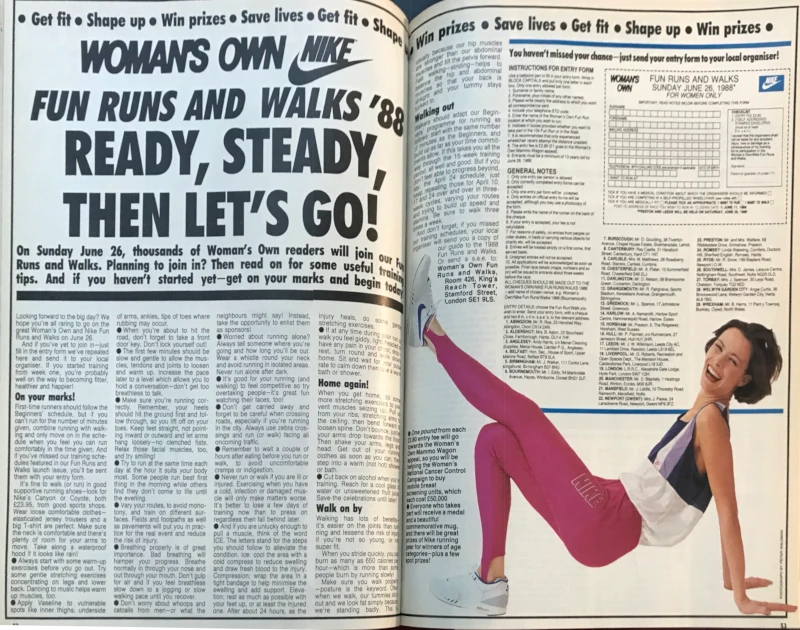

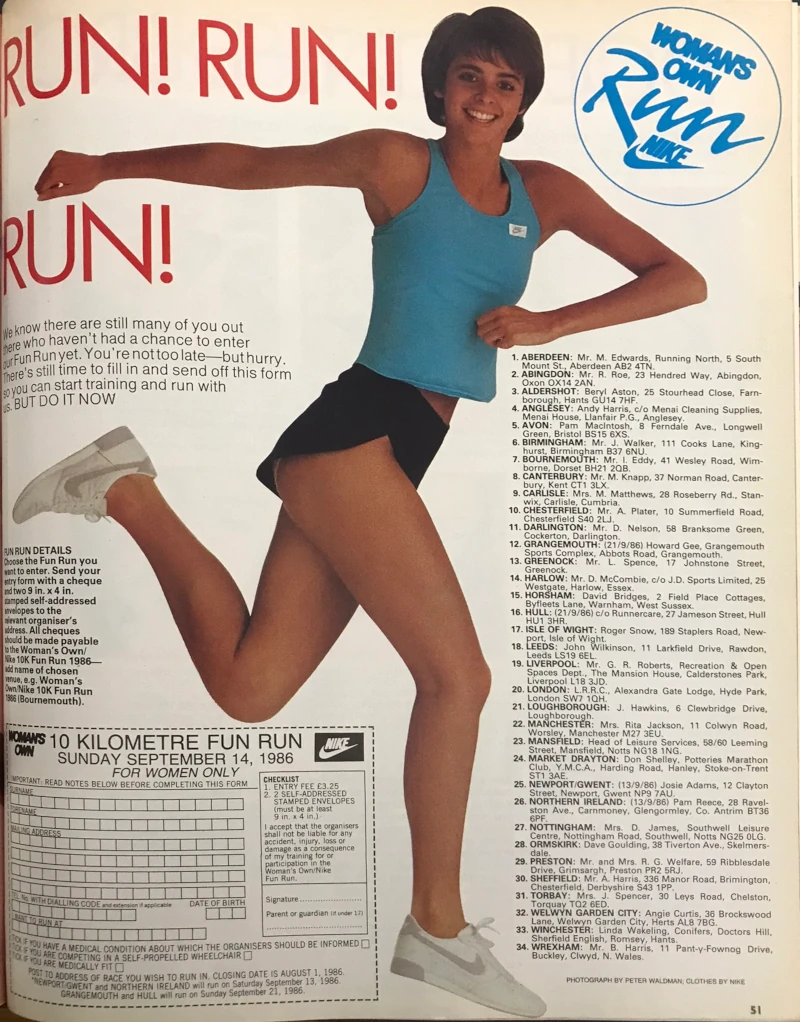

But by the middle of the decade, attitudes to running in women's magazines had started to change—though not overnight. A major milestone was the first Woman's Own/Nike Fun Run in 1984. 17,000 readers in different parts of the country ran or walked 10km and raised over £147,000 for the magazine's Save a Child Bone Marrow Unit Appeal. The event was so successful that the Fun Run became an annual fixture until 1988.

For five years, Woman's Own promoted women's running through this event. It announced each year's Fun Run with great fanfare, across pages that included training schedules for beginners, illustrations of warm-up exercises, and testimonials from previous participants, as well as the list of venues and entry forms. But running still rarely appeared anywhere else in the magazine. What was different about the Fun Run?

Jogging is a bit of a drag [but] trampolining is a new exciting experience—and demanding, too!

First, and most cynically, there was money at stake. In the first half of the decade, women's magazines did not usually promote exercise for its own sake. But when they did encourage women to take up sport, they mostly featured unusual hobbies. One 1985 article, complete with all-action photos of ordinary women flinging themselves through the air, urged women to try trampolining, skiing, badminton, or skating. Among them, Shirley, from Mitcham, Surrey, told readers, “Jogging is a bit of a drag,” but “trampolining is a new exciting experience—and demanding, too!”

No doubt Shirley did genuinely love the trampoline, but magazine editors were more cynical in promoting novel sports. Magazines needed to sell copies to make money—and that meant chasing the new. Everyone knew—or thought they knew—how running worked: stand up, put one foot in front of the other, move faster. Why would busy housewives need to read about that? The Fun Run provided a reason.

The quest for novelty had other benefits for magazine editors that usually worked against running. Most of their revenue came from advertisers. When magazines ran articles on sports, they followed up with special offers on equipment like foldaway exercise bikes, mini-trampolines, or aerobics videos. Features on sports that needed kit meant more cash for magazines. For most of the decade, running didn't fit the bill. It's a cheap form of exercise—all runners really need is a pair of trainers. In the 1980s, anyone looking for a high-tech fix had to settle for a hand-held stopwatch. There wasn't much to sell, and so little reason to include running in magazines.

Nike sponsorship of the Fun Run changed this. It meant that the magazine did not bear the costs of holding the event, but also that Woman's Own and its parent company IPC Magazines cemented a relationship with a major advertiser. As the event became more popular, it became possible to sell other kit to women who might not have paid for it when jogging had seemed just “a bit of a drag.”

Looking good equals feeling good and moving even better. So get your looks and yourself into top-performing gear for smooth running on Fun Run Day

The launch of the 1987 Fun Run event included a two-page fashion spread. The central photo showed a woman in top-to-toe Nike (accessorized with a Walkman), but inset boxes also promoted branded tinted moisturizers and waterproof mascaras. A week later, the magazine's latest installment of its training plan came with recommendations for the best sports bras. This information was useful to readers, but brand promotions also generated revenue for Woman's Own.

Second, because the Fun Run was a charity event, it fitted with the traditional model that women (especially mothers) should put others first. Magazines promoted this model of womanhood in lots of different ways.

Advertisements for washing powder, cooking sauces, and headache tablets showed women meeting everyone else's needs. True life features sanctified women who found out they were pregnant and chose not to have treatment for cancer in case it harmed the baby. “Supermum“ and “Woman of the Year“ competitions rewarded readers who juggled work and family life with raising money for the local hospital or nursing sick relatives.

Women with families often found it difficult to justify spending time running when society told them to prioritize their children and husbands. Magazines recommended stretches, floor exercises, and aerobics routines that could be done at home—in between housework, while the children were at school, or with a sleeping baby in the next room. But running meant going outside while someone else looked after the children or cooked the family meal.

It was easier for women to justify spending time exercising outside the home if it was for charity. Each year, a portion of the Fun Run entry fee was donated to charity, in addition to the funds participants raised through sponsorship. The charities that benefitted from the event were for children and women—Save a Child Bone Marrow Unit, Save the Children, and the Women's National Cancer Control Campaign. Women were less likely to feel selfish for taking time to train for the Fun Run because they were doing it to help others.

This might all sound a bit depressing—the magazines that millions of women bought every week only supported running when it generated a profit for them, or when it could be portrayed as for someone else's good. But Woman's Own/Nike Fun Run did have positive effects in promoting women's exercise—even if this change didn't happen overnight.

To really understand what was good about the Fun Run, we need to look in more depth at what women's magazines usually said about exercise. For much of the 1980s, these magazines did not see exercise as essential to women's health. They most often recommended exercise as part of a weight loss plan. The idea that ordinary women might exercise to feel healthy rather than to look good simply did not feature. There was little sense that some women might even enjoy exercise. The assumption was that most women hated their bodies and just wanted to be thinner. Exercise was a last resort if dieting wasn't enough.

“The very thought of exercise makes most of us wince,” started one article, before promising that regular “pep-up” action would get rid of “any flab that you could once literally pick up around your midriff” and improve the reader's sex life. It recommended “fun games at the beach” and swimming as “the best all-round exercise”—so long as the reader remembered to “rinse your hair after swimming to protect against dryness, and moisturize the skin to keep it smooth and supple”. But most of its two pages were spent outlining a “3-day summer energy diet” and adding up the amount of exercise needed to “burn up that 4 oz bar of chocolate”.

This obsession with weight loss did carry over into coverage of the Fun Run. Woman's Own enticed readers to participate to help them “get fit, lose weight, and shape up.” Reader testimony reinforced the body-shaping effects of running, whether it was the story of Belinda, who lost eleven stone in the course of training, or Helen from Dorset's claim that, ”At 47, I have a new lease of life—jogging is an antidote to stress, a major contributor to physical health and a weight controller”. The weekly training plans were often on the same page as diets.

But weight loss was not the only theme of Fun Run features. Instead, articles emphasized the positive effects of running. It helped to “put problems in perspective,” to meet “new friends,” and to provide “an escape from the stresses of work or family life—plus a sense of achievement and confidence in your own ability to set yourself a target and reach it.”

Fun Run participants enthusiastically agreed. Some readers who took part spoke about losing “flab,” but most emphasized instead that running made them “calmer,” “better, brighter, more wide awake,” and that they had “more energy for everyday life.” Ursula Travett, 56, “used to spend her spare time in front of the TV” but had now “joined the Southern Counties Veteran Association and I hope a lot of women my age take up running. I've more to talk about, more interest in life and I'm much more confident”.

At this moment in the mid-1980s, women's magazines started to tell their readers that running wouldn't kill them—even the most unfit reader could build up to 10km. Even if they found it difficult, they would feel better in body and mind—healthier, happier, and calmer. This was a huge difference from what magazines had told their readers in the previous half-century.

These positive accounts of running mattered even more because this wasn't the only message that magazines pushed about how women should see their bodies and health. Every single issue of Woman's Own in the late 1980s featured a diet programme. Journalists clearly found it difficult to keep up with producing so much weight loss advice—it's difficult to believe they expected readers to take seriously the Astro-diet, fish ‘n’ chip diet, hot potato diet, or the Eastenders diet (yes, there were jellied eels). But repeated so often, readers could not help believing that they should try to be slimmer, whatever it took.

For three months of the year, for five years in the 1980s, Fun Run features told women something different—that, yes, it could be fun to run. Articles on track runners Kate Fitzgibbon, Shireen Bailey, and Christine Boxer, who all took part in the Fun Runs at different points, provided women with role models. But so did all the testimony from “ordinary” participants—women who had not run before but were now burning to tell other potential runners about how it had improved their lives.

If you're wondering why what happened four decades ago matters, think about the influence these Fun Runs might have had. Maybe, just maybe, these effects trickled down the generations. We know that active parents encourage active children. We also know that girls are more likely to drop out of sport than boys. Daughters who see their mothers running know that women can do this.

Clearly still on a runner's high months later, 1984 participant Shirley Bray from Berkshire wrote, “I'm 49 and feel I could run until I'm 80. I cried when six-year-old Gemma called: ‘Come on, Grandma, you can do it!’ I cried again when my daughter came in 20 minutes later. Thank you for getting me fit”. Gemma, wherever she is, is 46 now. I wonder if she has daughters—and if she does, I wonder if she has ever told them, as they lace up their trainers before heading out, about cheering their great-grandmother over the finish line that day?

Tracey's work includes a wealth of research and publications, with her main focus being research into gender, body, and selfhood in twentieth-century Britain. She has also co-created a toolkit that uses historical sources to help adolescents think differently about emotional health and wellbeing in the present. You can find out more on her University of Essex profile page.